I had been stumbling around in the plot of a book I was writing for some time. I knew the protagonist couldn’t read and that books were disappearing. I was going for some kind of Alice Hoffman magical realism thing. Perhaps with a little humor since my book’s working title was “Too Dark to Read,” after the Groucho Marx quote: “Outside a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside a dog, it’s too dark to read.” But then in 1996, my daughter came through the door, crying, “Mom, they’re banning books!”

I had been stumbling around in the plot of a book I was writing for some time. I knew the protagonist couldn’t read and that books were disappearing. I was going for some kind of Alice Hoffman magical realism thing. Perhaps with a little humor since my book’s working title was “Too Dark to Read,” after the Groucho Marx quote: “Outside a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside a dog, it’s too dark to read.” But then in 1996, my daughter came through the door, crying, “Mom, they’re banning books!”

My daughter was a junior and an IB student in a North Carolina high school. She had a mean forehand and a voracious love for books, including the book in question, The Old Gringo by Carlos Fuentes. Fuentes is recognized as one of the most influential writers in Latin America. In fact, in 2006, he received the Four Freedoms Award for Freedom of Speech and Expression. Ironic, I know.

My first response was to sit down, read the book, and discuss it with my daughter. It is the story of celebrated American writer and journalist Ambrose Bierce, who mysteriously disapeared in Mexico during its civil war. Fuentes imagines the fate of Bierce among Pancho Villa’s troops in a tale that examines “the borders between men and women, dreams and reality, Mexico and the U.S.,” as Publishers Weekly put it.

What the censors in our town (parents of one of the students) objected to were explicit scenes between a young Mexican revolutionary and the American teacher, who falls in love with him. I had no problem with my 17-year-old daughter reading those scenes. But then I’ve never denied my daughter a book she wanted to read.

After an intense public meeting and a review by committee, The Old Gringo eventually was returned to the shelf and the IB curriculum. But in the process, my daughter’s English teacher, a favorite of many of the kids, decided to move on, perhaps to a place where teachers didn’t receive hate mail.

This incident had a huge impact on the direction of my book, Book of Mercy. Book banning in fictitious Mercy, North Carolina, became the conflict, and Antigone Brown, the woman who fights the censors, became the protagonist who ponders the same questions I had as I wrote letters in protest of the removal of The Old Gringo.

All too often, censorship is a parental issue. As Antigone says in Book of Mercy, “I want to protect my child from the world. But I also want to protect the world for my child.”

What I learned in writing this book and in raising my daughters is that books can never be allowed to disappear from the shelves without a squeak. We must say something; explode the discussion in letters, e-mails, tweets, and public meetings. We must never let censorship dissolve into the dark.

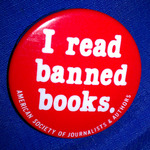

According to the American Library Association, on average about 500 books are challenged every year in the United States—and those are just the ones we know about. Some would say this is horrible. But I think if we didn’t have a way to challenge the actions of others, we wouldn’t be truly free.

So I accept that book challenges are necessary, but I also am happy when they fail.

Book of Mercy, a story about a woman who faces her greatest fear to save a town’s books, is available in paperback and on Kindle. Read more about Book of Mercy or check out an excerpt.